The part no one talks about isn’t replication. It’s what happens when replication breaks — and your system keeps saying everything is fine.

Most systems that need to be fast use a key-value store somewhere in the stack. Session state. Rate limits. Feature flags. Idempotency keys. Cached objects. These reads and writes sit on the critical path of user-facing latency, so even brief slowdowns ripple into timeouts, retries, and cascading failures.

The hard part is not making it fast. The hard part is making it correct — especially when machines fail, network packets get lost, and clients keep retrying at exactly the wrong moment.

This is a deep dive into how to design one from scratch: replication, failover, quorum, fencing, and every pathology that will keep your application up at all times in production. No hand-waving. No skipping the ugly parts.

Why This Problem Is Harder Than It Looks

key-value store is the “fast cupboard” behind many products. The pressure comes from the fact that availability and correctness fight each other during failures. If different replicas disagree about the latest value for a key, the system can accidentally “go back in time,” double-apply increments, or allow stale configuration to persist. Meanwhile, clients keep retrying, creating load spikes precisely when the system is least able to handle them.

A practical design must define which guarantees are non-negotiable — what “correct” actually means — then build replication and failover mechanisms that remain safe under partial failure, message delay, duplication, and reordering.

The design choice we’re making here: per-key strong consistency for acknowledged writes, over maximum write throughput. We accept coordination cost to prevent acknowledged-write loss during failover. Everything that follows flows from that single decision.

Where This Actually Breaks: Four Scenarios

Before we get into the design, let’s make the stakes concrete.

A multiplayer game stores each player’s matchmaking ticket as a key with a short TTL. A regional network blip partitions a subset of replicas. The store must avoid resurrecting expired tickets and must not “match” the same ticket twice after retries.

A checkout service keeps an idempotency record keyed by request_id for 24 hours. If a primary node crashes mid-write, a failover must not lose the record — or the payment flow double-charges after client retries.

An IoT gateway stores a per-device “last-seen sequence number” and rejects older messages. If two clients route to different replicas during failover, the store must not accept an older sequence number as new, or downstream state regresses.

A security policy engine reads feature flags and deny-lists from the store on every request. During replica lag, the system must not serve a stale “allow” decision after an administrator flips a critical flag.

Each of these is a correctness failure that looks like normal operation from the outside. That’s what makes them dangerous.

The Correctness Contract: Choosing CP

Before we deep dive, we have to address the elephant in the room: the CAP Theorem.

In a distributed system, you can have Consistency, Availability, and Partition Tolerance—but you only get to pick two. Because network partitions are inevitable, the real choice is between Availability (AP) and Consistency (CP).

The design choice we’re making here is a strict CP stance. We prioritize per-key strong consistency for acknowledged writes over maximum uptime.

What does that look like in the real world? It means that if the network collapses and a quorum cannot be reached, the system will choose to error out rather than serve “wrong” or stale data. We accept a localized outage to prevent a global state corruption. Everything that follows—the fencing, the quorums, the strict WAL—is in service of this single contract.

The Architecture, Top to Bottom

Here’s how the pieces fit together at a high level:

- Clients send

GET/PUT/DELETEand optional conditional updates (e.g., “set-if-version”). - A routing layer maps key → shard using a stable partition function. Each shard is replicated as a small replica group: one leader, multiple followers. This is a leader–follower replication model: a single leader serializes writes, followers replicate asynchronously and serve as failover candidates.

- Writes go to the leader, which appends to a durable log, replicates to followers, then commits based on a quorum rule.

- Reads go to the leader for strong consistency, or to followers with explicit staleness semantics and fencing rules.

- A membership service tracks who is in each replica group and who is leader.

- A background rebalancer moves partitions when nodes are added or removed.

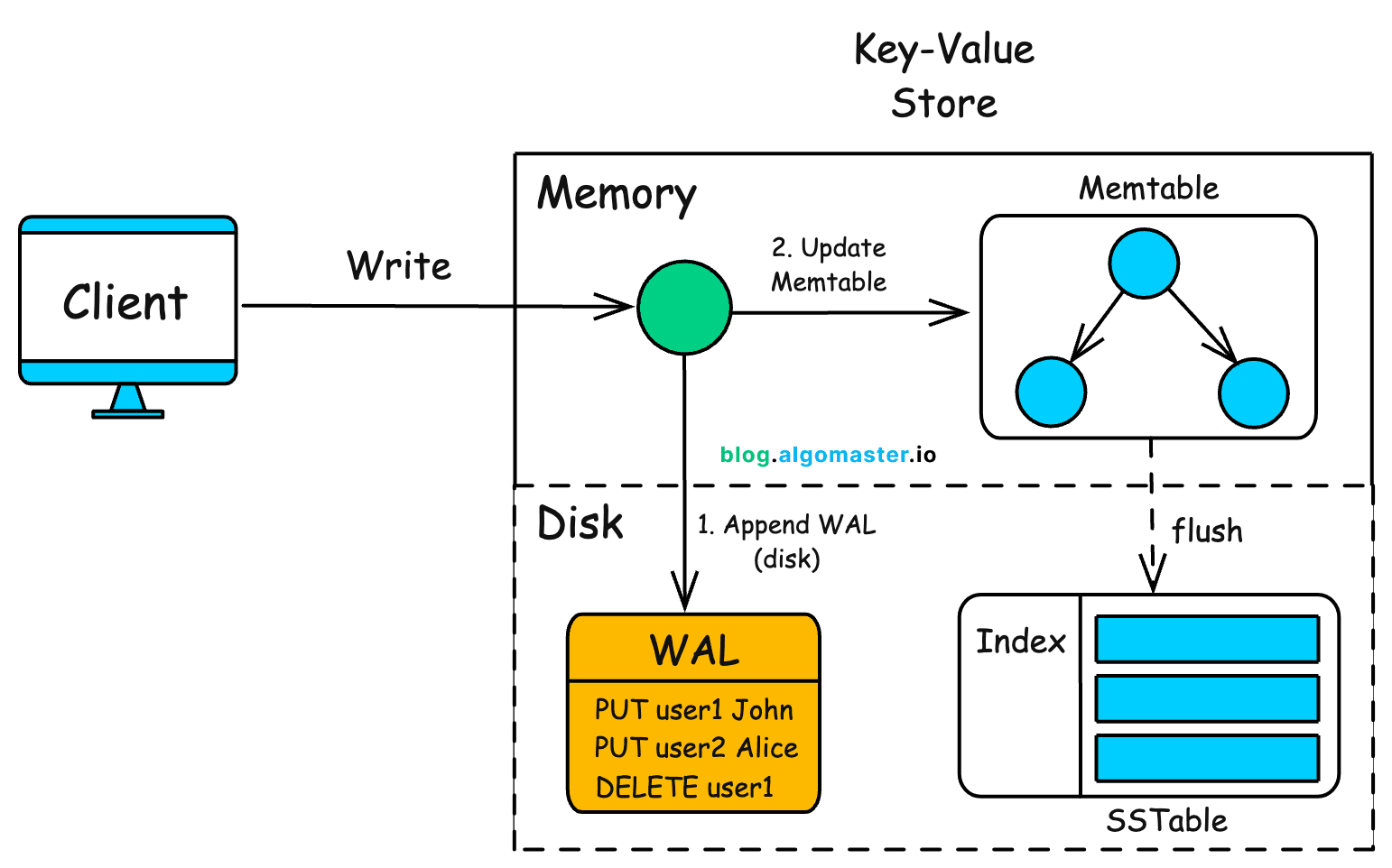

- A storage engine persists state using an in-memory structure, a durable log, and periodic snapshots.

That’s the skeleton. The rest of this post is about why each of those pieces is harder than it sounds. Two contracts matter more than the diagram.

First: what does “acknowledged” actually mean? In this design, an ack only happens after the write is durably persisted on a quorum and the commit point is advanced. Anything earlier is a promise the system cannot keep under failover.

Second: reads are not one thing. Leader reads are the default because they’re linearizable; follower reads exist, but only when the client explicitly accepts staleness or the follower can prove it’s caught up.

The Core Mechanisms

Consistent Hashing: The Art of the Balanced Ring

Imagine distributing thousands of unique items into a handful of buckets. If you use simple modulo division, adding one bucket forces almost every item to move. Consistent hashing solves this by placing both keys and nodes on a ring. A key looks clockwise until it hits the first available node.

The problem: physical machines aren’t equal. Some are faster, some have more memory. So we use virtual nodes — mapping one physical machine to hundreds of points on the ring. This achieves a statistical distribution that stays stable even as nodes flicker in and out of existence. At scale, adding a node only moves roughly 1/N of the keyspace.

This stability is the foundation of everything else. If your partition scheme forces large data movements when a single node changes, every scaling event becomes a crisis.

Trade-off: Minimal remapping during scaling vs. increased memory for routing tables. In practice: In a 50-node cluster with 150 virtual nodes per physical node, adding one node moves ~2% of the data (close to the theoretical 1/51 = ~1.96%). Without virtual nodes, hash distribution variance can leave the hottest node handling 2x average load.

The Heartbeat Pulse: Distinguishing Sleep from Death

How do you know if a node is dead or just slow? The network is a liar. A delayed heartbeat might mean a crashed server, or it might mean a congested router.

Too aggressive detection triggers unnecessary failovers. Too slow, and the system hangs while users wait. Simple timers aren’t enough. Phi-Accrual failure detectors don’t just say “dead” or “alive” — they output a probability of failure based on historical network behavior. The system stays calm during minor hiccups and acts decisively when the probability crosses a threshold.

This matters especially under load. Migration and rebalancing add network pressure. A system with hardcoded timeouts starts triggering false failovers at exactly the moment it can least afford the disruption.

Trade-off: Fast detection vs. stability (avoiding “flapping” where nodes repeatedly join and leave). In practice: A 500ms spike triggers a warning. The system waits for 3 consecutive missed pulses before electing a new leader. Hardcoded timeouts are the leading cause of cascading failures in production.